My second IBH Blog Post will draw from the 3rd Diverse Perspective – “Student explains or illustrates perspectives of people in their historical context”.

World War I is known to many as a conflict with foundations set in Europe, but a setting of the war that is seldom discussed in sources is colonial Africa. While the Central and Allied powers fought on the East and Western fronts, the “Imperial Battles” took place in Kenya, a UK colony, and the German territories including Togo, Cameroon, Namibia and German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi). Like the tensions that erupted in the Balkans, there were disputes leading up to WWI within the African colonies. Incidents such as the two Moroccan Crises demonstrate the extent to which European powers engaged in competition for control of African territories.

Contrary to generalisations that warfare in the African fronts was small-scaled, the statistics suggest otherwise. According to SanBeck.org, over 750,000 troops were mobilised in East Africa alone to form the Allies’ indigenous force. Britain, France and Belgium coordinated a plot to attack and control German colonies; this plan was seen as a way to weaken supply of sources and hurt the German establishment. As WWI broke out, the British Navy took steps to blockade German East Africa. In mainland German East Africa, territories were claimed by Belgium and the UK. Cameroon and Togo would be overtaken by French colonial forces, primarily assembled from French West Africa, Madagascar and French Equatorial Africa. The German territory of Namibia was also swiped by the British in Southern Africa, along with the piece of the Congo taken post-2nd Moroccan Crisis (France took this territory back).

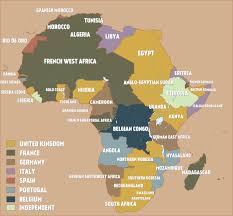

In order to understand how battles in Verdun or Gallipoli were synchronised would lead to fighting in Yaoundé or Dar es Salaam, the geographic context must be established.

In July 1914, France, Britain, Russia were the major powers constituting the Allied force, with minor forces including Belgium. There were colonies established by the French, British and Belgian administrations in Africa prior to the war; Germany was the only true Central power with territories in the continent. The Allies knew that a point through which the Kaiser’s Empire could be penetrated was the control of the colonies. German Cameroon, East and Southwest Africa were all significant sources for mineral and agricultural exports.

At the conclusion of the war in 1918, Germany would surrender its African colonies to the Alliance; France, the UK and Belgium would split the Empire’s former territories amongst themselves.

Below is a list of the African Allied and Central colonies in 1914. These groupings can be used to understand how the Alliance was able to reach German colonies with their neighbouring territories. This proximity shows why France, Belgium and the UK would’ve been interested in taking German colonies even prior to the war.

French African Colonies in 1914

French West Africa: Senegal, French Sudan (Mali) Mauritania, Niger, Dahomey (Benin), Ivory Coast, Guinea

North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco

French Equatorial Africa: Gabon, Ubangi-Shari (Central African Republic), Chad, French Congo State (Congo-Brazzaville)

British African Colonies in 1914 (South Africa is excluded as it became a Union in 1910)

West Africa – Nigeria, Gold Coast (Ghana), Sierra Leone, The Gambia

North Africa – Egypt/Sudan

East Africa – Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, Nyasaland (Malawi), British Somaliland

Southern Africa – Northern Rhodesia (Zambia, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Basutoland (Lesotho), Swaziland

Belgian Colonies in 1914

Belgian Congo (Congo-Kinshasa)

German Colonies in 1914

German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda)

German Southwest Africa (Namibia)

German Cameroons (Cameroon)

Togoland (Togo)

Sources

Beck, Sanderson. “East Africa 1700-1950.” East Africa 1700-1950 by Sanderson Beck, SanBeck.Org, www.san.beck.org/16-12-EastAfrica.html#a7.